Hip dysplasia is a congenital disease that affects mostly large breed dogs, although any breed can get it, and even cats can have a problem with their hip sockets.

Hip dysplasia is a laxity in the socked of the hip joint where the head of the femur fits into the pelvis. It causes weakness and lameness to the rear quarters, and eventually leads to painful arthritis. This arthritis goes by several names; degenerative joint disease, arthrosis, osteoarthritis.

Classification

There is an organization called the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA) that has studied this disease and has a large database of information. They will certify a dog as hip dysplasia free at two years of age. This standard of care has been a boon in reducing this disease, especially for breeders.

The OFA group consists of 25 board-certified radiologist that evaluate the hips of dogs based on a specific set of radiographs. The OFA has 7 different categories based on an X-Ray of a dogs hips:

- Excellent

- Good

- Fair

- Borderline

- Mild

- Moderate

- Severe

Cause

Many factors work together to cause this disease, which is a combination of a dog genetically inclined to get this disease, interacting with environmental factors that bring about the symptoms. These environmental factors excess calcium in the diet of puppy food for large breed dogs, along with obesity, high protein and calorie diets, and a lack of or too much exercise.

Large breed dog food is especially formulated so that they do not stimulate excessive growth of the bones. These allows the bones to grow without hurting the growth plates.

The breeding of dogs that already have hip dysplasia is one of the primary reasons the disease is still present. A dog that has hip dysplasia in one socket is prone to having a problem with the ligaments of the knee in the other leg (anterior cruciate rupture).

On occasion trauma to the cartilage can be a cause.

Pathophysiology

During the degenerative process the cartilage that lines the hip joint, called hyaline cartilage, is damaged. The damage results from the abnormal forces on the cartilage from the deformed hip socket. Small fractures can occur in the cartilage also. Eventually an enzyme is released that degrades the joint further and decrease the synthesis of an important joint protectant called proteoglycans. The cartilage becomes thinner and stiffer, further compromising its ability to handle the stresses of daily movement and weight bearing.

As the problem progresses more enzymes are released, which now affect the precursors to proteoglycans, molecules called glycosaminoglycans and hyaluronate. Lubrication is negligible, inflammation occurs, and the joint fluid can no longer nourish the hyaline cartilage. This vicious cycle continues until pain occurs. The body attempts to reduce this pain by stabilizing the hip joint.

New bone is deposited at the joint, both inside and out, along with some of the ligaments and muscle attachments to the area. This causes thickening and a decrease in the range of motion. This is the actual arthritis noted on a radiograph, which will not go away, and will continue to progress.

Symptoms

They range from mild to severe, depending on the age and size of your dog, along with the degree of hip dysplasia. Some symptoms to watch for are:

Slow getting up after resting or sleeping

Reluctance or slow moving up the stairs.

A hopping gait in the rear legs

Stiffness when moving

Not being able to complete a long walk

Stopping during a walk and even sitting down during a walk

Weakness in the rear quarters

Discomfort or pain when you touch the rear quarters

Lameness or limping on one leg

Please keep in mind that large breed dogs are stoic. Do to their propensity to please you, these dogs can see fine on the outside but are painful on the inside. Watching for subtle signs is important.

Breed Predispositions

Many dogs can develop hip dysplasia. Dogs that were commonly affected years ago, like German Shepherds and Labrador Retrievers, still get the disease, but not as commonly as before.

According to the OFA some of the breeds with the highest prevalence are:

| Bulldog | Pug | Otterhund | Clumber Spaniel |

| Neapolitan Mastiff | St. Bernard | Boykin Spaniel | Sussex Spaniel |

| American Bulldog | Newfoundland | American Staffordshire Terrier | Bloodhound |

| Bullmastiff | Chesapeake Bay Retriever | Golden Retriever | Gordon Setter |

| Rottweiler | Chow Chow | Old English Sheepdog | Kuvasz |

| Norweigan Elkhound | Giant Schnauzer | German Shepherd | Bernese Mountain Dog |

| English Setter | Black and Tan Coonhound | Shih Tzu | Staffordshire Terrier |

| Welsh Corgi | Beagle | Briard | Brittany |

| Bouvier des flandres | Welsh Springer Spaniel | Curly Coated Retriever | Polish Lowland Sheepdog |

| Portugese Water Dog | English Springer Spaniel | Pudel Pointer | Irish Water Spaniel |

Diagnosis

Hip Dysplasia is diagnosed based on a history of weakness or lameness to the rear legs, especially after exercise or when first getting up after resting. Some young dogs will bunny hop when running, and might lie down on their stomachs with their legs stretched behind them. It is possible to palpate joint laxity on some dogs that are anesthetized (we call this the Ortolani sign). Sometimes we will feel grinding, called crepitus, in the hip joint as we move the leg around the socket.

Many variables affect the degree of lameness. They include age of onset, caloric intake, degree of exercise, and weather. To further add to the complication, pets with terrible looking hips on radiographs might act as if nothing is wrong, while others with barely discernible changes on their radiographs might be severely lame.

Radiography

Radiography (X-ray) is the definitive way this disease is diagnosed. It is not perfect though, since a dog can be hip dysplasia free on the radiograph (phenotype), but can be genetically predisposed to the disease (genotype). These dogs have the potential to be carriers of the disease, yet show no symptoms themselves.

In order to make a diagnosis, the pelvis must be aligned, and the legs extended. This can only be done when a dog or cat is under sedation. We take two views of the pelvis:

- VD (ventrodorsal)- In this view your dog is on its back when we take the radiograph of the pelvis

- Lateral- In this view your dog is on its side

Your dog needs to be mature to be able to diagnose hip dysplasia accurately. If it is too young the growth plates are not fully formed.

These are the pelvic radiographs of a 3 month old pup with obvious growth plates. The gaps in the bone are cartilage, which does not show up on a radiograph.

At 6 months of age you can still see the growth plates, but it is still too early to make a diagnosis of hip dysplasia

The pelvis radiographs of a mature dog with normal hips, compare it to the dog below that has hip dysplasia

This dog has moderate changes that indicate it has hip dysplasia on both sides. The sockets are not as rounded as they should be, and the head of the femurs are slightly flattened.

This dog has hip dysplasia in its right hip socket (see the R marker for the right side)

This is a bad case of hip dysplasia on both sides

This is severe hip dysplasia

Dogs are not the only species that gets hip dysplasia. It can also occur in cats, although not as commonly as in dogs. Maine Coons are are the cat breed that is most commonly affected.

This is an elderly cat with hip dysplasia

The white arrows outline the large amount of stool in the colon of the above cat with feline hip dysplasia. It is painful for this cat to squat to have a bowel movement, as a result it gets severely constipated.

Other diseases that cause lameness or soreness in the rear legs can mimic hip dysplasia. These include rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament in the knee, Intravertebral disk disease (IVD), panosteitis, and degenerative disease of the spinal cord called degenerative myelopathy, a disease that occurs in German Shepherds.

Medical Treatment

Medical therapy might help in some cases. It depends on the size of your dog, what its function will be in your household, age, and severity of the problem. You might need to try several treatments until you find the one that works. Many of these treatments need to be used in combination with other medical therapies.

Medical therapy will not cure the problem, and in most cases painful arthritis will set in. Early surgical intervention is usually the best course of action. It is not uncommon to radiograph your dog’s pelvis when it is already under anesthesia for a spay (OVH or ovariohysterectomy) or neuter.

Swimming in a pool if your dog is comfortable with it can be beneficial. Hydrotherapy in a tub supervised by a veterinarian certified in rehabilitative medicine is also helpful.

Non-Drug

Acupuncture, Laser Therapy, and VNA are excellent treatment choices in many cases because they are effective without the use of drugs. Our Alternative Medicine page has detailed information.

Gentle passive range of motion exercises might help. Use of the food J/D (joint diet) is also recommended. There is also a version of J/D called Metabolic and Mobility that decreases weight in obese dogs while also providing treatment for the arthritis. It contains extra amounts of omega-3 fatty acids which might help reduce joint inflammation. One of these foods should initially be tried on all dogs with hip dysplasia.

An additional treatment modality that has yielded great success in treating hip dysplasia is called VNA. It is a non-invasive and non-painful way to stimulate the nervous system to help the hip dysplasia syndrome. It is used as

This 18 year old dog has been treated with VNA for years and is doing great

Drugs

Many drugs have been used to control the pain associated with the secondary arthritis that occurs with hip dysplasia. Some of these drugs are extremely effective, and can provide a dog with a high degree of relief from pain. They only mask symptoms though, and do not cure the problem.

Buffered aspirin and ascriptin® (aspirin with maalox) are readily available over the counter remedies. Tylenol should not be used in dogs because of its potential for side effects. Tylenol is NEVER used in cats because it can cause a serious disease called methemoglobinemia.

NSAID’s (Non Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs) are highly effective prescription medications. The work by inhibiting the release of prostaglandins, leading to less inflammation in the joints. They should be given prior to any bout of exercise. Some dogs will vomit or have diarrhea on these medications. Giving the medication on a full stomach and using GI protectants like Pepcid AC can minimize this problem. Common NSAIDS are Galliprant and Rimdayl.

Their use in labradors should be carefully monitored for signs of liver problems. Any dog that is on these drugs long term should have a blood panel taken to monitor internal organ function, especially kidney and liver.

Nutraceuticals are popular arthritis treatments, primarily because they are thought of as more natural than drugs. Humanoids use them commonly. They provide the raw material that enhance they synthesis of glycosaminoglycan and hyaluronate. Controlled studies are lacking to determine their true effectiveness. Oral versions take at least one month to become effective. A great advantage is their lack of side effects. Oral versions include Cosequin®, Synovicar®e, Glycoflex®, arthramine®, and MaxFlex®.

Their effect is variable, and ranges from nothing to a significant improvement. They are not going to cause harm, so they are worth trying. Just be objective about their ability to help just because they are more natural than drugs.

An injection of a drug called Adequan® is helpful in many cases. This is an FDA-approved disease modifying drug. It contains a polysulfated glycosaminoglycan that inhibits the enzymes in the joints that cause inflammation. It is given as an injection, up two twice per week, and stopped after 8 treatments.

We can’t predict which medications will work best in an individual case. Trying different ones, even using some of them in combination, can let you determine which is the best approach in your dog.

Surgical Treatment

Most cases of hip dysplasia, especially in younger dogs, are treated surgically. One of the surgical specialists we consult with will make the determination of which procedure is the most appropriate. Three main types of surgery are performed:

- Femoral Head Ostectomy (FHO) or Excision Arthroplasty

- Triple Pelvic Osteotomy (TPO)

- Total Hip Replacement (THR)

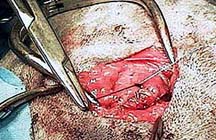

This area contains graphic pictures of actual surgical procedures performed at the hospital.

1. Femoral Head Ostectomy (FHO) or Excision Arthroplasty

In this procedure the head (or ball) of the femur is removed. The remaining part of the femur forms a false joint with the muscles, ligaments, and tendons in the area. Even though this false joint is not as good as a real joint, there is a significant reduction in pain.

Almost any sized dog can have this procedure even though it is much more effective in smaller dogs. Obese dogs and those with significant loss of muscle do not do as well. Compared to the other types of surgery this one is much more basic, yet many pets that have this surgery return to almost normal function.

This are the hips of Mickey, a very active Australian Shepherd. He has hip dysplasia on both sides. FHO surgery will be performed on his right hip.

After the skin incision is made the muscles are separated to give visualization of the femoral head. It is gently rotated and brought up as far as possible.

A special air powered drill is used to cut the neck of the femur at just the right angle

The angle in the cut of the femoral neck is apparent. also present on the head of this femur is a piece of the round ligament, one of the structures that anchors the head of the femur into the socket.

An opening remains where the head of the femur used to reside. The remaining bone will form a false joint, and return this pet to almost 100% function.

The muscles that were separated and cut are now carefully sutured. These muscles are necessary for normal movement of the false joint that will soon form.

This is what remains after the surgery. Mickey healed rapidly after the surgery and is running around as fast as before, according to his worried mom.

We also do the FHO procedure when there is a fracture at the neck of the femur. This link has detailed pictures of the surgery. Click on the photo below to see how we did an FHO surgery on this dog with a fractured pelvis and neck of the femur.

2. Triple Pelvic Osteotomy (TPO)

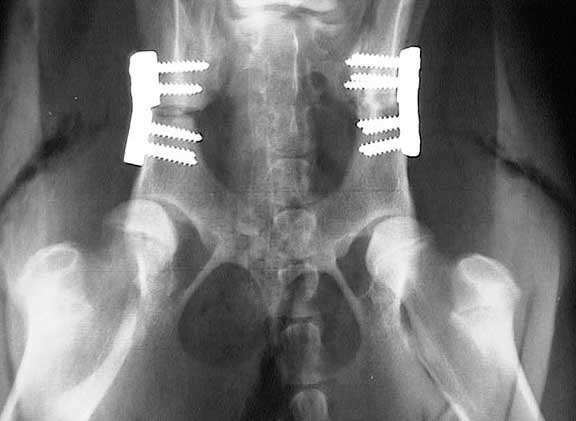

This surgery is used in large breed dogs no older than 10 months of age. Candidates for this surgery can only have mild hip dysplasia and no signs of secondary arthritis. During the procedure the pelvis is cut and rotated slightly so that the head of the femur has a tighter fit into the socket. Since the pelvis is being cut it needs to be stabilized with bone plates.

The pelvis is cut in 3 locations. The locations of these cuts allows the proper rotation of the hips.

This is the final result after a TPO surgery. These two plates are angled to provide the proper pelvic rotation.

3. Total Hip Replacement (THR)

In this procedure the neck and head of the femur are replaced with stainless steel or titanium implants. This is a highly specialized procedure performed only by select veterinarians. It is used in young dogs that have achieved most of their skeletal growth and in adult dogs that weigh at least 40 pounds.

It can be used in dogs that already have secondary arthritis, unlike the TPO. It has a high success rate but has to be performed carefully because if post operative complications occur they can be difficult to control.

This is the end result of the surgery. These implants now make up the ball and socket joint, and will remain fully functional for many years.

Prevention

This is achieved by neutering pets that have the disease. Dogs can be screened for this problem by taking radiographs of their hips at 2 years of age. If they are certified free of hip dysplasia by the Orthopedic Foundation of America (OFA), there is much less of a chance they will sire offspring with the problem.

It is best to purchase large breed dogs only if their parents are OFA certified to be hip dysplasia free.

No guarantee can be given when breeding hip dysplasia free dogs radiographically that their offspring will not develop the disease. A dog can be hip dysplasia free on a radiograph, yet still carry the genetic predisposition to this disease that will be transmitted to its offspring.