Cushing’s Disease (also known as hyperadrenocorticism- (Cushing’s is easier to pronounce, so stick with that word) results when the adrenal glands secrete an excess amount of cortisone. It is named Cushing’s because that is the name of the doctor that discovered this disease.

It is the most common endocrinopathy (hormone disease) encountered in older canines. This disease is the exact opposite of another endocrine problem in canines called Addison’s disease (hypoadrenocorticism).

This is a complex hormonal disease that does not lend itself to a simple explanation or an easy diagnosis. Some pets have the symptoms, yet the tests for Cushing’s are negative. Other pets have positive test results, but minimal symptoms that do not warrant treatment. Test results can change when repeated a short time later. Everything can be vague and in a continual state of flux.

This complexity will be explained in this page, so get comfy and get ready to get your brain stimulated. Take a break if needed, and come back to it when you are ready to learn more.

We have a summary page on Cushing’s if the explanation on this page is too detailed for your needs.

This detailed page will emphasize Cushing’s disease in dogs, with an explanation of how it differs from cats at the end.

This page contains graphic photos.

Medical Terminology

Several medical terms and abbreviations relate directly to Cushing’s:

| cortisol– cortisone produced by the adrenal glands | atrophy– decreased size of an organ |

| exogenous cortisone– supplemental cortisone | hypertrophy– increased size of an organ |

| HAC – hyperadrenocorticism | polyuria– excess urinating |

| CRH– corticotropin releasing hormone | polydipsia– excess drinking |

| polyphagia– excess appetite | PU/PD– polyuria and polydipsia |

| glucocorticoids– mostly cortisol, and a small amount of cortisone | mineralocorticoid-hormone that affects sodium and potassium |

| hypoglycemia– low blood glucose level | iatrogenic– caused by something a person does as opposed to happening naturally. |

| adrenalectomy– surgery to remove the adrenal gland. | ACTH– adrenocorticotrophic hormone |

| hepatomegaly– enlarged liver | adrenomegaly– enlarged adrenal gland |

| anabolic steroid– testosterone and its equivalent | PD– pituitary dependent |

| catabolic steroid– cortisol and its equivalent | AT– adrenal tumor |

Adrenal Gland Anatomy

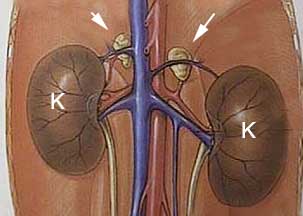

The adrenal glands are small paired glands buried in fat in the front of each kidney. Even though they are small, the cortisol they secrete, along with their other functions, have great significance to normal physiology. These guys are small but mighty, as you are about to learn!

The arrows point to the paired adrenal glands in front of each kidney. The extensive blood supply to the kidneys and adrenal glands is apparent. In the diagram they are easy to see. They are not so easy to see during ultrasound or exploratory surgery because normally they are small and buried in fat. They do not show up on an X-ray unless they are calcified.

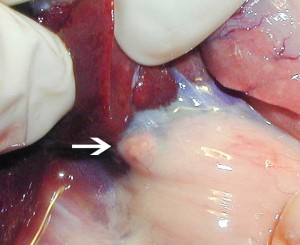

This is a normal ferret right adrenal gland, just under a lobe of the liver, which is pulled forward by the surgeon’s fingers

This is a normal ferret left adrenal gland (just above the hemostat) buried in fat. The left kidney is the structure to the right.

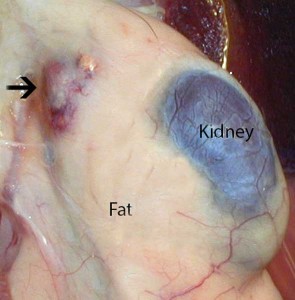

This is a picture of an enlarged left adrenal gland (arrow) that is buried in fat near the kidney (K). I is from a ferret that has adrenal gland tumor, so the gland is inflamed and easy to visualize. This is not necessarily the case in dog and cats with adrenal gland tumors.

The internal architecture of the adrenal gland is made up of several distinct zones.

Cortex

The cortex (outer shell) of the adrenal gland is made up of 3 anatomical parts:

-

Zona Glomerulosa

This is the outer layer of the adrenal gland. This section secretes the mineralocorticoid aldosterone. Aldosterone is vital for proper sodium and potassium regulation. Aldosterone has a role in maintaining blood pressure.

-

Zona Fasciculata

This is the next layer as you go inward, and produces the glucocorticoid cortisol. The cells in this area are the ones that cause Cushing’s.

-

Zona Reticularis

As we continue inward we come across this section that secretes the sex hormones known as androgens (male sex hormones), estrogen (female sex hormones), and sex steroids. These are usually secreted in such small amounts as to be of no major significance in healthy animals.

Medulla

This consists of the very center of the adrenal gland. It secretes hormones called catecholamines. The two important ones are epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine.

Adrenal Gland Physiology

These tiny organs have a profound influence on many internal organs. The hormones they secrete work in unison with other internal organs, particularly the liver, and have an enormous effect on physiology.

These hormones interact with many other hormones that have the opposite effect, usually in some type of feedback mechanism that is monitored by the brain. This interaction is complex, so only a summary of adrenal hormone physiology is presented.

The adrenal glands secrete several important hormones, most of which are synthesized from cholesterol. We will explain 3 of them; cortisol, aldosterone, and epinephrine:

Cortisol

Cortisol is a hormone that is essential for life. Cortisol maintains a normal blood glucose level, facilitates metabolism of fat, and supports the vascular and nervous systems. It affects the skeletal muscles, the red blood cell production system, the immune system, and the kidneys.

It is considered a “catabolic steroid”. This means it takes amino acids from the skeletal muscles and, with help from the liver, converts them to glycogen, the storage form of glucose. These functions are the exact opposite of “anabolic steroids”, the drugs that weight lifters take to increase muscle mass. The end result of this is an increase in the level of glucose in the bloodstream.

The hormone called insulin has the opposite effect on blood glucose, adding to the complexity of this system. You can learn more about insulin by going to our diabetes mellitus page.

The level of cortisol in the bloodstream continually fluctuates as physiologic needs vary. Surgery, infection, stress, fever, and hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) will cause cortisol to increase.

This continual fluctuation adds to the difficulty of diagnosing Cushing’s, because the amount of cortisol in the bloodstream is so variable. A test taken at one moment in time might have different results if taken later.

To control the level of cortisol the hypothalamus and pituitary gland in the brain secrete chemicals into the bloodstream called releasing factors. In the case of the adrenal glands , the hypothalamus secretes a hormone called corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH).

It goes to the pituitary gland and stimulates it to release a hormone called adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH). It is the amount of ACTH circulating in the blood stream that tells the adrenal glands (specifically, the cells at the zona fasciculata) how much cortisol to secrete.

There is a negative feedback loop that allows the hypothalamus and pituitary gland to refine precisely how much cortisol circulates in the bloodstream. The more cortisol secreted by the adrenal glands, the less CRH and ACTH secreted.

This allows the body to precisely refine the level of cortisol, and to change the level rapidly due to changing physiologic needs.

Numerous internal organs are affected by cortisol:

-

Muscles

Cortisol is needed for proper muscle action, yet too much can cause the muscles to atrophy (shrink). This is due to their catabolic effect. This means that they literally cause the body to break down the amino acids in the muscle fibers in order to increase the blood glucose (sugar) level. Cortisol does this in a complex mechanism that involves the liver. The end result is the muscles become smaller. When this occurs at the abdominal muscles the abdomen appears pot bellied.

-

Bone

Bone is made up of a protein matrix and calcium, both of which are affected by cortisol. Excess cortisol affects the protein matrix, decreases calcium absorption from the intestines, and increases calcium excretion by the kidneys. Skeletal mass decreases and bones become weaker.

-

Skin

It causes atrophy of hair follicles and sebaceous glands, which leads to alopecia (hair loss). Elastic tissue under the skin is also affected, leading to thinner skin and adding to the pendulous abdomen. The disruption in the elastic tissue of the skin can also cause calcium changes in the skin. This might lead to areas where calcium builds up in small nodules. In cats the skin changes can become severe, and are referred to as fragile skin syndrome.

-

Vascular System

Cortisol is required for maintaining the integrity of the lining of blood vessels. An excess will lead to thinning of these walls and the potential for rupture. The end result is a hematoma. Cortisol also increases the number of circulating red blood cells and helps maintain blood pressure.

-

Central Nervous System (CNS)

Cortisol is necessary for the normal maintenance of brain functions. It can interfere with sleep and change the mood. You might notice these effects if your dog has Cushing’s or is given supplemental cortisone for treatment of a disease.

-

Liver

Excess cortisol will increase the workload on the liver as it converts amino acids to glycogen. Pets with Cushing’s will commonly have an enlarged liver, known as hepatomegaly. You will be shown a picture of an enlarged liver on an x-ray in the diagnosis section.

-

Kidney

An increase of cortisol increases the blood flow (also called GFR-glomerular filtration rate) to the kidneys. This will result in an increase in the amount of water and waste products filtered by the kidneys. Our kidney disease page has more details. This is one of the reasons why canines with Cushing’s drink and urinate excessively (PU/PD), and urinate a dilute urine.

-

Immune System

This is one of the more profound functions of cortisol. It decreases the inflammatory process and helps minimize an over reaction of the immune system to foreign bodies or infections. Unfortunately, it also suppresses the immune system to the point that the body has a hard time mounting a proper response.

- The body is now more susceptible to infections, especially those caused by bacteria. This is one of the reasons why we might prescribe antibiotics when we prescribe cortisone if we suspect any type of bacterial or fungal infection.

Mineralocorticoids

Aldosterone is the principal mineralocorticoid secreted by the adrenal glands. This hormone is secreted as a response from the kidneys when fluid volume in the bloodstream is decreasing. It involves other hormones called renin and angiotensin. The end result is an increase in sodium in the bloodstream, with a corresponding increase in blood volume and blood pressure.

This hormone also interacts with and affects potassium levels. To further complicate the picture, ACTH also has an affect here, just like it does with cortisol.

This part of adrenal gland physiology is not significantly altered in Cushing’s. Addison’s disease, which is the production of too little cortisone, has a greater affect on aldosterone.

Epinephrine (Adrenaline)

This compound, technically called a neurotransmitter, also has hormone-like properties. It is a very powerful chemical that effects all organ systems. It acts very rapidly, with effects remaining only for a short period of time. It is the primary reason the body has the ability to respond to an emergency. This physiologic mechanism is also known as the “flight or fight” response.

Upon stimulation of the central nervous system (ex.-fear or pain), the adrenal medulla is stimulated to secrete epinephrine into the bloodstream. We are all familiar with what happens next. The pupils dilate, the heart rate and blood pressure increase, and the palms get sweaty.

Internally, the body is increasing the blood glucose level, the breathing passages are opened up, more red blood cells are secreted into the circulation, blood is shunted away from the skin and other internal organs, and blood flow is increased to the brain and skeletal muscles.

All of this has the effect of bringing the brain and skeletal muscles extra glucose and oxygen, and accounts for the extra boost of awareness and energy we all feel at this time.

Cause of Adrenal Gland Disease

There are four causes to adrenal gland disease:

- Pituitary Dependent (PD)

- Non-Pituitary Dependent (AT- Adrenal Tumor)

- Iatrogenic

- Ectopic ACTH Syndrome

Pituitary Dependent (PD)

Up to 85% of all Cushing’s cases in canines fall into this category. The pituitary gland is invaded with a slow growing cancer called an adenoma. This causes it to secrete an excess amount of ACTH.

The cells in the zona fasciculata area of the adrenal glands respond to this excess ACTH by hypertrophying (enlarging) and secreting excess cortisol. It is this excess of cortisol that is circulating in the bloodstream that causes the symptoms we see in this disease.

This pituitary gland tumor can remain slow growing and not effect the pet any more than inducing Cushing’s disease. In 10-20% of these tumors they enlarge to the point that they will cause significant neurologic symptoms.

Unfortunately, some of these neurologic symptoms mimic those seen as side effects to the medication used to treat Cushing’s. This is a prime example of how complicated medicine is, and why we strive for evidenced based medicine to help unravel the complexity.

Brain tumors are best diagnosed using an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging). This boxer has a large white tumor in its brain.

Non-Pituitary Dependent (AT)

In up to 15% percent of Cushing’s cases there is an actual tumor of one of the adrenal glands (sometimes both are involved). The tumor enlarges and secretes excess cortisol in the bloodstream.

This excess cortisol is monitored by the hypothalamus and pituitary in the negative feedback mechanism, causing them to secrete less ACTH. Less ACTH in the bloodstream will cause the other adrenal gland (if it does not also have a tumor) to atrophy (shrink).

The benign version of this tumor occurs 50% of the time, and is called an adenoma. These canines usually live a normal life. There is a small chance this adenoma can progress to a macro-adenoma, where the prognosis is not as good.

The malignant version, which occurs the other 50% of the time, is called an adenocarcinoma. It can invade the primary vein returning blood back to the heart (called the vena cava), and spread from the adrenal gland to the liver, lung, kidney, and lymph nodes. Dogs with adenocarcinoma usually do not live more than a year.

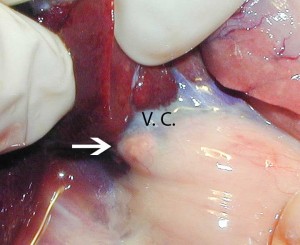

The white arrow points to a small and normal right adrenal gland in a ferret. A lobe of the liver has been pulled forward so you can see the adrenal gland. The dark blue structure running horizontally is the vena cava (VC)as it courses past the liver towards the heart. The close proximity of the adrenal to the vena cava and liver shows how easily a malignant tumor here can spread into the bloodstream and lodge elsewhere in the body.

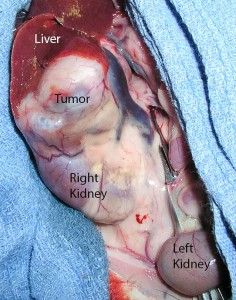

This is a huge right adrenal tumor, almost as large as the kidney below it. Notice how the vena cava (dark blue vertical structure to the right of the tumor) goes in a different direction that the pictures above. Removing the large adrenal gland is not possible without also removing the vena cava.

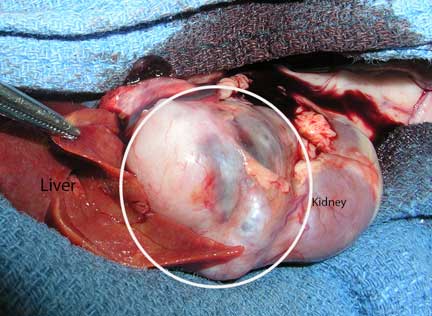

This ferret adrenal tumor is so large that i is bigger than one of the liver lobes and bigger than the left kidney

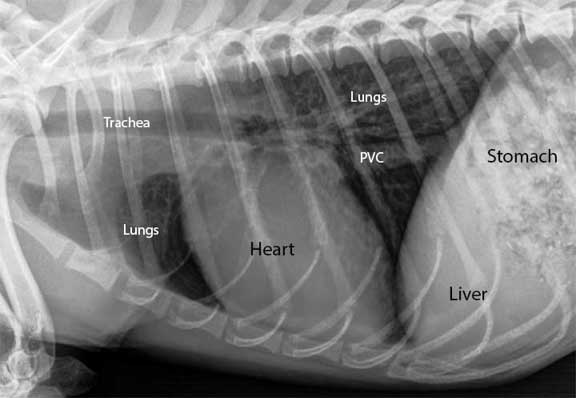

This radiograph shows the vena cava (labeled PVC for Posterior Vena Cava) in the chest after it has passed by the adrenal gland on its way to return venous blood back to the heart

Adrenal tumors are a common problem in ferrets. The adrenal tumor in this case does not secrete excess cortisol, so technically the disease is not called Cushing’s. The tumor causes an excess secretion of sex hormones, causing a different set of symptoms when compared to the dog and cat.

Iatrogenic

Exogenous (external or supplemental) use of cortisone is very common in medicine. It is a highly beneficial drug used to treat a wide variety of diseases. In some cases it is used as an emergency drug to literally save a life. Cortisone is beneficial in several disease categories:

- Inflammation

- Immune system

- Neoplasia (cancer)

- Cerebral edema (brain swelling)

- Shock

Long term use of cortisone, in oral, injectable, or even topical form, might cause an animal to have the symptoms of Cushing’s disease. It all depends on the type of cortisone used, the dose it is used at, and the duration of use. As a general rule, once the original symptoms of the disease are treated with cortisone, we recommend decreasing its use, stopping its use, or finding an alternative drug.

Sometimes this is not feasible though, especially in immune system diseases. The symptoms of these diseases far outweigh the potential side effects from this exogenous use of cortisone. An example is Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD).

The level of cortisone that results from this exogenous use will cause the adrenal glands to atrophy. The negative feedback loop tells the brain there is plenty of cortisol in the bloodstream, so the pituitary secretes less ACTH. The pet has the symptoms of Cushing’s because cortisone is being introduced into its body, not because the adrenal glands are producing it in excess amounts.

Exogenous cortisone goes by several names. They come in injectable, oral, and topical forms, and tend to be more potent than the cortisol that is naturally produced by the adrenal glands.

Some of the more common ones are:

- Prednisone

- Depo-Medrol

- Dexamethasone

Ectopic ACTH Syndrome

This is a rare version of Cushing’s that does not fall into any of the above categories. It can be found in association with cancer in the canine.

Symptoms

Some dogs with Cushing’s disease show the classic symptoms, while other show only a few vague symptoms. These symptoms are variable, and in a state of constant flux, which is consistent with endocrine (hormonal) disease.

The classic symptoms are:

Polyuria/polydipsia (PU/PD)- This is excess urinating and excess drinking of water. It is one of the first signs of the disease, and usually precedes the other symptoms by a significant period of time.

Several other important diseases cause these symptoms also, notably liver disease, kidney disease pyometra, and diabetes mellitus (sugar diabetes).

Pot bellied abdomen to the point a dog might look pregnant. It is due to hepatomegaly and abdominal muscle weakness (the mechanism of which was described above in the physiology section).

Thin skin and usually symmetrical hair loss along the trunk. The hair might grow in lighter in color or lose its luster. It might not grow in well at all. Calcium deposits under the skin, called calcinosis cutis, occur on occasion. Secondary skin infections called pyoderma are common also. The skin might also be hyper-pigmented.

Muscle wasting (sarcopenia) over the head, shoulders, thighs, and pelvis.

Polyphagia- excess appetite. This is often interpreted by clients as being healthy, since most people think of a sick pet as not eating well. In this case your canine is over-eating, which is consistent with Cushing’s.

Other occasional symptoms include:

Pruritus (itchy skin)- due to secondary bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infections of the skin

Panting- due to affects on the lungs or the respiratory center in the brain

Obesity

Anorexia (poor appetite)

Straining to urinate or blood in urine due to a urinary tract infection or bladder stone

Weakness

Depression

Aggression

Lethargy

Corneal plaques

Irregular heat cycles in female dogs

Testicular atrophy in males and clitoral enlargement in females

Emesis (vomiting) due to pancreatitis

Ataxia (incoordination), blindness, circling, and seizures due to a large pituitary tumor or spread of a malignant adrenal tumor

Lameness due to a ruptured cruciate ligament

Intra-abdominal bleeding near the kidneys (retroperitoneal space) resulting in anemia, weakness, and abdominal pain

Diagnosis

A thorough approach is needed for a correct diagnosis of Cushing’s. In every disease we encounter we follow the tenet’s of the diagnostic approach to ensure that we make an accurate diagnosis, and also so that we do not overlook some of the other diseases that are common in pets as they age.

Nature works in complex ways, and just because you have one disease does not mean you cannot get another one to complicate the matter. These co-morbidities are common in older pets, another reason we need to be thorough in our diagnosis so as not to miss them.

The best way to diagnose this disease is with history and physical exam. If your canine has PU/PD, polyphagia, alopecia, muscle weakness, and excessive panting, then it most likely has Cushing’s. The adrenal screening tests are used to verify the diagnosis and confirm treatment is needed.

Some dogs have the normal symptoms of Cushing’s, but routine blood sampling does not bear this out. In these cases we will repeat the adrenal screening tests at some time in the future, or even perform abdominal ultrasound to look at the actual glands. These glands are small, and a veterinary radiologist is needed oftentimes to find them and determine if they are diseased.

1. Signalment

Cushing’s tends to be a problem that affects older dogs, usually greater than 6 years of age, with a median age of onset at around 10 years. The disease tends to have a slow and gradual onset, so the early symptoms are easily missed.

Several canine breeds are prone to getting Cushing’s:

- Yorkshire Terrier

- Poodle

- Beagle

- Boston Terrier

- Boxer

- Dachshund

Females and males get it at about the same frequency. Neutered pets might be at higher risk of Cushing’s.

2. History

Cushing’s disease is suspected in any pet that has some of the symptoms described above, particularly the skin symptoms and the PU/PD. It is important to remember that some dogs do not show any symptoms early in the course of the disease. This is another reason for yearly exams and blood and urine samples in dogs and cats 8 years of age or more.

Since dogs with this disease do not have a poor appetite usually (they have the opposite as explained in the symptoms section above), owners will delay in bringing their dog in for an exam. They assume a good appetite means their dog is doing fine. They misinterpret the excessive appetite (polyphagia) as being a good sign, when in reality it’s a sign of disease.

Most people wait until a dog, that is normally housebroken, is now urinating in the house. This delay can make it difficult to treat, and will frustrate some people to the point they are contemplating euthanasia.

Other historical findings include skin infections that recur after antibiotic therapy is stopped. Some dogs have a history of pruritus (itchiness) if pyoderma is present. A history of poorly controlled diabetes mellitus might also clue us in to Cushing’s.

3. Physical Exam

Routine physical exam findings might include:

Pot bellied abdomen

The abdomen of this dachshund is pot bellied due to Cushing’s. It could also have been due to fluid buildup from cancer or heart disease. An enlarged liver from a disease other than Cushing’s can cause this also.

An enlarged liver (hepatomegaly) might be palpated, along with smaller muscle mass (atrophy) in general.

Bruising (hematoma) might be observed under the skin, or when a blood sample is obtained.

Skin infections and wounds that do not heal or recur after antibiotics are stopped.

This dog has hair loss with a secondary skin infection called pyoderma

Blood pressure might be elevated. This might cause a detached retina, picked up by an ophthalmic exam.

Heart disease, initially noted with the stethoscope as an increased heart rate, an irregular heart rate, or a murmur.

4. Diagnostic Tests

Several tests are used as an aid in making this diagnosis. Each test has its advantages and disadvantages.

Skin Scraping

Skin scrapings are usually negative in Cushing’s, although demodex is possible as a secondary problem due to the immunosuppression effect of cortisol. Long term use of cortisone orally can also predispose a pet to demodex due to its immunosuppressive effects.

Blood Panel

A CBC (complete blood count) and biochemistry panel should be run on every dog 8 years of age or more, especially if they have any of the symptoms of Cushing’s.

The CBC might show an increase in the number of red blood cells (RBC’s) and/or an increase in platelets (thrombocytosis). It might also show an increased WBC (white blood cell count), called leukocytosis. When these white blood cells are broken down, there are usually more neutrophils (neutrophilia), less lymphocytes (lymphopenia), and less eosinophils (eosinopenia).

These white blood cell abnormalities can also be caused by the “stress response”. It is due to excess epinephrine and cortisol secreted in response to the actual process of taking the blood sample (those people that have passed out when their blood was taken are an extreme example of this). The excess cortisol secreted by the adrenals in the stress response is temporary, and part of normal physiology. It is not caused by Cushing’s disease.

Cholesterol, blood glucose. triglycerides, and liver enzyme tests (ALT) might be elevated in Cushing’s. If a thyroid test is run it might be low or borderline normal.

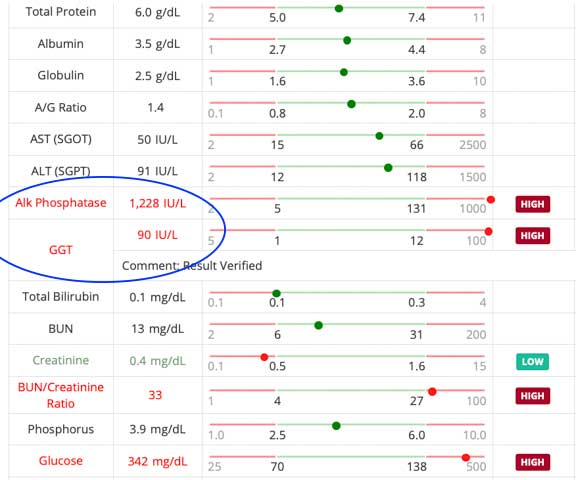

An elevated alkaline phosphatase (Alk Phos) is a consistent finding in Cushing’s. This is an enzyme that is located in the bile production area of the liver. The excess cortisol influences this enzyme, although growing animals, fractures, obstructions of the bile ducts, liver disease, drugs, pets with diabetes mellitus, and pets with cancer can all cause an elevated Alk Phos. A significantly increased Alk Phos alerts us to keep Cushing’s in our tentative diagnosis list.

This dog has a mildly elevated liver enzyme test and an elevated Alk Phos. If the signalment, history, and physical exam do not make us suspect Cushing’s we probably will not proceed to adrenal screening tests. This dog should be examined, and the blood should be checked every 3-6 months to see if these abnormalities are increasing.

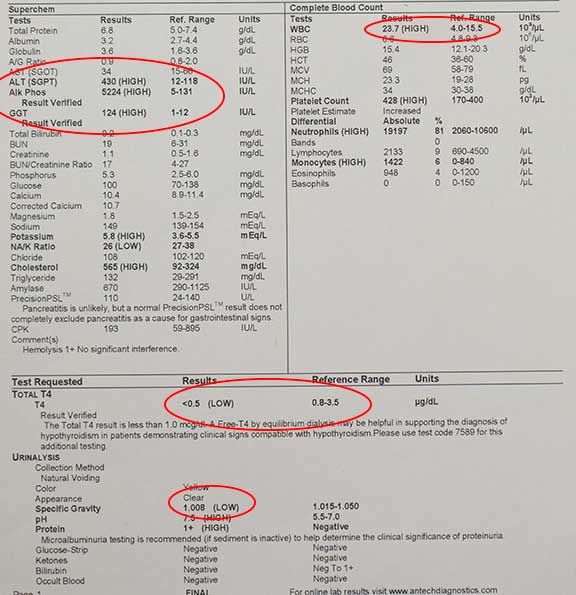

This dog with Cushing’s has several problems on the blood panel that are secondary to the Cushing’s:

Increased WBC- 23.7

Severely increased liver enzymes- Alk Phos- 5224

Low thyroid- <0.5

Low urine Specific Gravity- 1.008

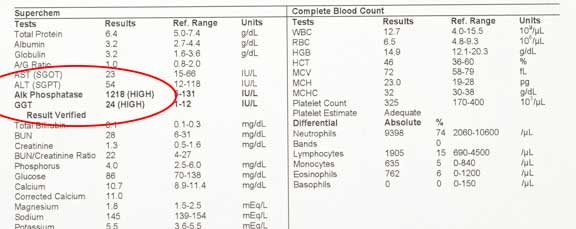

This is the blood panel on the same dog with Cushing’s two weeks after starting treatment. The WBC’s are back to normal, and the Alk Phos is much less. As time we goes on and we continue treatment, we can expect these values to continue to improve.

Urinalysis

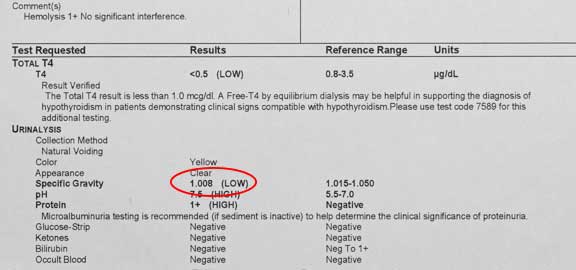

A normal specific gravity in a dog should be at least 1.025, and there should be no or minimal protein, glucose, WBC’s, or bacteria, as a general rule. With Cushing’s, the specific gravity of the urine might be low, the protein might be elevated, and a urinary tract infection might be present because of excess glucose in the urine.

The urinalysis of this dog shows a low specific gravity 1.008, which is consistent with Cushing’s

Skin Biopsy

This test can give us an idea that Cushing’s is the cause of a skin problem. Many of the changes that are noted microscopically when evaluating the biopsy are also seen in other diseases, so it is not specific for Cushing’s. In spite of this fact, skin biopsies give us a large amount of information in skin conditions.

A skin biopsy is easy to perform under a local anesthetic with our special skin biopsy instrument

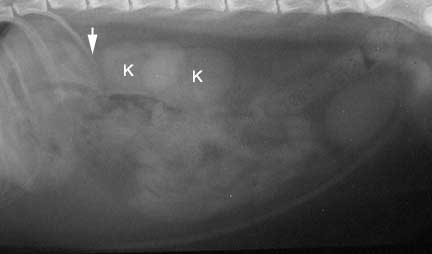

Radiography

Radiography might be of value if the adrenal glands are calcified (happens in up to 50% of adrenal tumors), otherwise the adrenals do not show up on a radiograph. Hepatomegaly can be seen on the radiograph, along with problems associated with other diseases in pets this age, so a radiograph can be highly beneficial to help rule them out.

Radiography might also show osteoporosis (poor bone density) and calcification of soft tissue, both of which could be due to excess cortisol.

In this lateral view (laying on its side) of the abdomen, the kidney (K) closest to the arrow is the right kidney. The arrow points to where the right adrenal gland is located, although it cannot be seen since it is not calcified. The whitish area between the K’s is normal, and is caused by the effect of the 2 kidneys as they overlap.

This is a VD (ventral-dorsal, or laying on its back) view of a dog. The left kidney (K) is labeled, and the arrow points to where the left adrenal gland is located. There is some calcification in this radiograph, but it is not at the adrenal gland. Can you see it?

This is what a calcified adrenal gland might look like on a radiograph

The liver is large and rounded, consistent with a liver problem second to many diseases, including Cushing’s

Ultrasound

This test can be highly beneficial in this diagnosis. The adrenal glands can be measured, and their internal architecture (called parenchyma) can be analyzed. It is not feasible to visualize all of the distinct different zones of the adrenal gland though.

Other internal organs are also checked, giving us a substantial amount of information from just one test. A common incidental finding when we do a routine ultrasound on a dog suspected of having Cushing’s is to find this pet also has IBD (Inflammatory Bowel Disease).

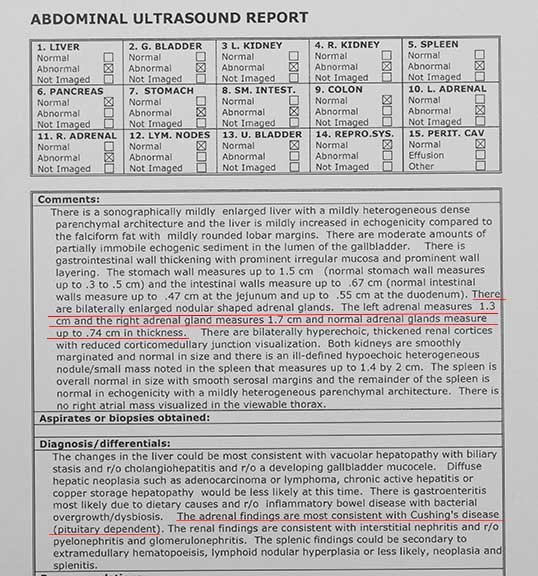

This is the report enlargement of both adrenal glands

Screening Tests Background

This is the most reliable way to confirm a diagnosis of Cushing’s disease, and also where results get muddy sometimes. These tests evaluate the interactions that are occurring between the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the adrenal gland. The interaction between these glands is known as the hypothalmic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

The first goal is to determine if Cushing’s disease exists. The next step is to determine if it is pituitary dependent (PD) or non-pituitary dependent (an adrenal tumor- AT). You might want to go back to the Cause Section above for a review before proceeding further.

Testing this axis is not as easy as it sounds. The mammalian body is a dynamic system with thousands of chemical reactions and interactions occurring simultaneously. Also, levels of cortisol are in a continual state of flux, depending on the time of day, the season, medications, diet, and stress levels.

Underlying diseases like Urinary Tract Infections can affect these screening tests, and need to be controlled first. Because of all this variability, interpreting these tests can be problematic, and it is not uncommon to repeat them in the future to look for consistent findings and monitor trends.

We prefer to perform these tests when the stress level (for example a car ride to our hospital) is not high. It might be worth it to take your dog for a short walk after you park the car to let it settle down. One of the rests requires a 8 hour hospital stay.

The normal values in animals calculated by a particular lab are called reference values. They reflect 95% of the population, statistically the same thing as the values that fall under the bell shaped curve.

Not every animal falls perfectly into this range, so there is always a degree of interpretation needed in determining whether a value is abnormal or not. Eventually, it boils down to a determination of probabilities, coupled with experience in diagnosing diseases in animals. This applies to all diagnostic test, not just for Cushing’s.

Sometimes the test results are borderline for the disease. In these cases we use other test like ultrasounds, or we repeat the tests 1-3 month down the road.

Two important concepts of laboratory testing relate directly to Cushing’s- Sensitivity and Specificity:

Sensitivity

The sensitivity of a test refers to the ability of that test to detect diseased patients. A Cushing’s test that is 95% sensitive will diagnose Cushing’s in 95% of all dogs with Cushing’s disease. 5% of the dogs in this scenario will have Cushing’s, even though the screening test for Cushing’s says they don’t have the disease.

Specificity

The specificity of a test refers to the ability of the test to detect only diseased patients. A Cushing’s test that is 95% specific means that 95% of the time if the test is positive for Cushing’s, the animal really does have Cushing’s. This means that 5% of the time the test will say an animal has Cushing’s disease when in reality it does not.

Animals that do not have Cushing’s disease might show up positive on these tests, while others that have the disease might be negative on these tests. Many times we have to play the odds based on probabilities. Due to this limitation in testing we recommend using these tests in combination, and repeating them if they do not give clear cut answers.

These tests sometimes come back as positive for Cushing’s when in reality other diseases are affecting the cortisol level. Some of these diseases (called non adrenal illness) include liver disease, chronic kidney disease, urinary tract infection, skin diseases, and uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. Also, cortisone and anticonvulsants can give false positives.

Screening Tests for Cushing’s

The most common screening tests are as follows. Now might be a good time to take that bathroom break before reading about them. There will be a summary of these tests at the end.

Urine cortisol:creatine ratio

In this test the level of cortisol in the urine is measured and used as an indication of the cortisol level in the bloodstream. Creatinine is measured to adjust for different levels of urine dilution. Our kidney page has more information on creatinine.

This test is useful as a screening tool when our differential diagnosis (you know what that means because you read theDiagnostic Process page) does not put Cushing’s on the top of the list. For example, we might use it in a pet that has PU/PD, but not the other signs of Cushing’s. It works in both dogs and cats.

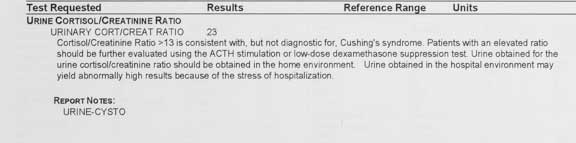

This one came back positive, which means this dog might have Cushing’s, and it warrants further testing to confirm. If it was negative, we would probably not do any further testing for Cushing’s, unless we felt the test was improperly obtained, or the dog had significant symptoms of Cushing’s.

This test is easy to perform because all that is needed is a urine sample. We recommend you obtain this sample at home in the morning just after your pet wakes up. Bring it to us immediately for analysis by our lab. Obtaining it at home will minimize the stress of a car ride and a visit to our hospital, both of which will normally increase the level of cortisol in the bloodstream (remember the stress response?), thus affecting this test.

A high level of cortisol in the sample is suggestive of Cushing’s. Unfortunately, up to 80% of dogs that don’t have Cushing’s will also have an increased level. This means that the specificity is low. If the cortisol:creatinine test comes back normal, then it is unlikely that Cushing’s is present, and we do not routinely recommend the following screening tests. A cortisol:creatinine ratio test that is high means Cushing’s might be present, and needs one of the other screening tests to determine if Cushing’s is indeed present.

ACTH Stimulation

This test checks for Cushing’s and Addison’s Disease. We tend to use this screening test when we suspect Iatrogenic Cushing’s. It is also used to monitor therapy on pet that is on medication for Cushing’s and Addison’s disease.

When a dog or cat is given ACTH by an injection the adrenal glands are stimulated to produce cortisol. By measuring this cortisol with a blood sample we can determine what reserve the adrenal glands have in the production of cortisol.

This is what we use for the ACTH stimulation test

This test is very specific for Cushing’s, so false positives are rare compared to other screening tests. It is not as sensitive as other screening tests, particularly the LDDS test. 20% of dogs that have Cushing’s will be negative on this test. For this reason it is sometimes used in combination with the LDDS test.

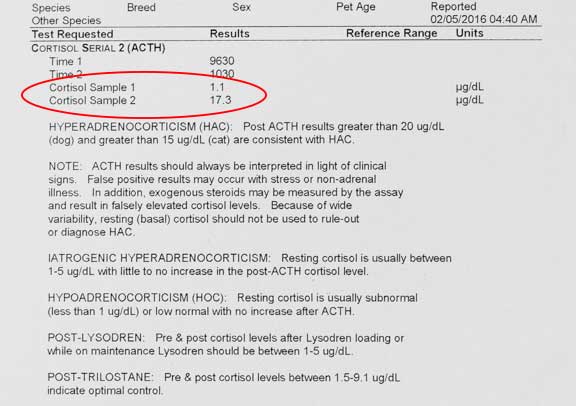

This dog does not have Cushing’s according to this test, but it might also be a false negative if the symptoms of Cushing’s are present

This is the only test that can distinguish between iatrogenic and naturally occurring Cushing’s. It is the only test that gives reliable results for a dog that has been on cortisone recently. It does not distinguish between pituitary dependent (PD) and non-pituitary dependent (AT-adrenal tumor).

A blood sample is taken to measure the resting cortisol level before ACTH is given. Two hours after the ACTH injection is given a blood sample is taken again to measure the level of cortisol. This two hours gives the ACTH injection time to stimulate the adrenal glands to produce cortisol.

In the dog, if the second test of cortisol is much higher than the first, it is suggestive of Cushing’s 80-95% of the time. It does not necessarily tell us if it is PD or AT, because this exaggerated response will occur in 85% of PD Cushing’s, and also 50% of those with AT Cushing’s. This test is not as reliable in cats, only 51% of cats with Cushing’s will show an exaggerated response.

If there is a reduced level of cortisol on the second blood sample, then either the dog has Addison’s disease or iatrogenic Cushing’s. This reduced response also occurs in dogs that are receiving Mitotane or Ketaconazole therapy for Cushing’s.

Between 5% and 20% of dogs that have Cushing’s (either PD or AT) will not show the exaggerated response expected with this disease. If this test is normal or borderline in a dog we suspect Cushing’s in these dogs then the test should be repeated at a later date, or the LDDS test should be performed.

Low Dose Dexamethasone Suppression Test (LDDS)

This is probably the best test when the history, physical exam, and routine blood panel and urinalysis are consistent with Cushing’s. We also use it when we feel there is no chance of Iatrogenic Cushing’s. It might also help differentiate between PDH and AT, but that is better determined by the HDDS test (High Dose Dexamethasone Suppression test). It only works in dogs because cats get a significant number of false positives.

It is sensitive for Cushing’s, because 85% to 100% of the time it finds a Cushing’s disease that is present. This means it does not diagnose a pet that has Cushing’s disease up to 15% of the time.

Its specificity is low though, meaning it might come back as positive for Cushing’s between 44% and 73% of the time when the dog does not have Cushing’s. If we are not sure of the results because of this variability, we might also perform an ACTH stimulate test.

This dose of dexamethasone (which is a version of cortisone) suppresses the adrenal gland from producing cortisol in normal dogs, but not those with Cushing’s. It achieves this suppression by interfering with the negative feedback mechanism. The dexamethasone is monitored by the brain as an excess of cortisone in the bloodstream, so less ACTH is secreted, and therefore less cortisol is secreted by the adrenal gland.

In this test an injection of Dexamethasone is given and cortisol levels are measured at 4 hours and 8 hours after the injection. Like the ACTH stimulation test, a pre-injection blood sample is taken to measure the resting cortisol level.

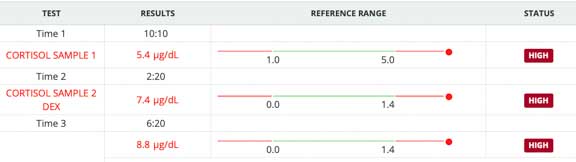

Here are the LDDS test results on a dog that we suspected of having Cushing’s

High Dose Dexamethasone Suppression Test

This test is not used as a routine screening test. It comes into play when a dog already has Cushing’s and you want to be certain that it is not that rare case that is an adrenal tumor.

The protocol for this test is similar to the LDDS test, except of course, a higher dose of dexamethasone is injected. A dog with an adrenal tumor does not suppress cortisol levels from the baseline sample.

Summary of Cushing’s Screening Tests

Urine cortisol:creatinine

In some dogs with Cushing’s the excess cortisol that circulates in the blood stream will spill over into the urine. If this test is positive then a dog might have Cushing’s. If it is negative, there is a good chance it does not have Cushing’s.

ACTH Stimulation

A positive on this test gives a reasonably good chance that a dog has Cushing’s. It will not catch all dogs with Cushing’s, so a dog with a negative test might still have the disease. In general, we use this test to monitor patients that are already being treated for Cushing’s or Addison’s.

LDDS

This test will catch most dogs that have the disease, and is the test of choice for Cushing’s on dogs that have symptoms. A negative on this test means that most likely the dog does not have Cushing’s. A positive on this test indicates that a dog might have Cushing’s. It is the most popular adrenal screening test.

If a dog has symptoms that are typical of Cushing’s, but all of these tests come back negative, we recommend repeating these tests every 1-3 months to monitor.

5. Response to Therapy

One of the tenets of the diagnostic process is whether or not a treatment that is instituted actually corrects the problem. This usually applies to Cushing’s. You should note significantly less PU/PD, improved skin, and a more active pet if the treatment is successful.

Then again, we might have the correct diagnosis and treatment, yet your animal does not get better because there are other diseases (co-morbidities) like dental disease (gingivitis and periodontal disease) causing the lack of response to treatment. Nobody ever said nature does things in simple ways.

The reddish gums above these teeth with tartar are inflamed, a sign of gingivitis

Treatment

Before we discuss treatment we need to keep things in perspective. This is a chronic disease, and most dogs do not die from this disease. We tend to treat when the symptoms described previously are affecting a dog’s quality of life or are a major nuisance to a pet owner. We do not routinely treat just because the tests say your dog has Cushing’s- the symptoms of the disease need to be present also.

It might be years before this dog shows signs, if any, of Cushing’s. At the same time, we want to start treatment at the optimal time just as the symptoms of Cushing’s starts. Any dog diagnosed with Cushing’s should have follow up tests performed periodically to look for changes to help in this decision.

Dogs that have significant symptoms of Cushing’s that have been confirmed by screening tests need to be treated to prevent potentially serious diseases secondary to Cushing’s that include Diabetes Mellitus, Urinary Tract Infection (UTI), pancreatitis and High Blood Pressure (Hypertension).

This Staph bacteria was cultured from a urine and numerous antibiotics were tested to find the most effective one. The S means this Staph infection is sensitive to everyone of these antibiotics in this in vitro test. This is a rare occurrence, and shows no antibiotic resistance.

Treatment can be drawn out, and involves significant time and expense to monitor your pet after we treat it. Also, in some dogs, treatment can sometimes lead to side effects that are more serious than the symptoms of this disease. One of these side effects includes a rare death, so we do not undertake treatment of this disease lightly.

This disease tends to occur in older dogs that commonly have other problems. Some dogs die of other diseases before the symptoms of Cushing’s become a significant problem. Treating Cushing’s does not necessarily give your pet a longer life. The goal of therapy is to give your pet a better quality of life.

Underlying problems need identification and treatment. The biggest underlying, overlooked, and serious problem we commonly find in dog with Cushing’s is Dental Disease. You saw an example of a dog with gingivitis earlier.

If your dog is hypothyroid the problem needs to be corrected with supplemental soloxine. Internal organ problems like kidney disease and liver disease need treatment for a successful Cushing’s outcome. Urinary tract and skin infections need to be cleared up with the use of antibiotics, and underlying diabetes mellitus needs to be regulated with insulin.

Some dogs with large tumors of the pituitary gland might initially respond to medical therapy for pituitary dependent Cushing’s. The Cushing’s symptoms, especially neurologic, might recur as the tumor progresses.

Several different treatment modalities have been developed for Cushing’s. Some are for Pituitary Dependent Cushing’s, some are for Iatrogenic Cushing’s, and some are for adrenal tumors.

Pituitary Dependent (PD) Cushing’s Treatments:

Trilostane

This is the newest treatment for this disease, and the one we recommend in most cases. Trilostane is an inhibitor of an enzyme called 3-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. This enzyme is involved in the production of several steroids including cortisol. Inhibiting this enzyme inhibits the production of cortisol.

It will be given daily for the rest of your dog’s life

It is usually given once per day, but in some dogs, especially those with Diabetes Mellitus, the Cushing’s symptoms might not diminish at the once daily dosing and the medication needs to be given twice per day (every 12 hours). It always needs to be given with food for proper absorption. Some dogs do not absorb this drug even when treated with food. In that case, another drug needs to be used.

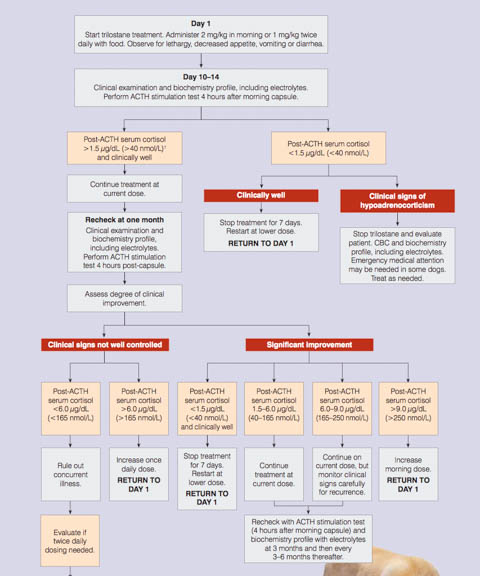

When we use this drug to treat your dog’s Cushing’s we will also give you a detailed flow chart of what to look for at home and when to return for additional test and monitoring. The ACTH stimulation test is used for monitoring purposes. Do not fast your dog on the day we do this test, and give the Trilostane as you always do.

This flow chart is helpful to monitor the adequacy of adrenal suppression by Trilostane

If your dog does not respond to Trilostane, and the ACTH stimulation test indicates inadequate adrenal suppression, the dose or frequency of administration might need to be changed.

If you are using the compounded version of trilostane, and your dog is not responding, switch to the name brand of trilostane (Vetoryl from Dechra).

Mitotane (o,p’-DDD)

This drug has been used to treat this disease for 30 years, and is know by the trade name of Lysodren. It selectively destroys the zona fasciculata and reticularis, effectively limiting the amount of cortisol that these areas of the adrenal gland can secrete.

Pets that are on insulin for diabetes mellitus need to have their mitotane and insulin doses adjusted downwards. It should be administered with meals to enhance its absorption. This drug is first administered at a loading dose for 7-10 days.

Side effects are not uncommon:

- lethargy

- emesis (vomiting)

- diarrhea

- anorexia (poor appetite)

- weakness

- ataxia (in coordination)

Side effects are due to the cortisol level being reduced below normal levels. Even if the cortisol level does not go below normal levels, a rapid decrease in elevated cortisol levels to the normal range can still cause these symptoms.

You need to closely observe your pet when it is on mitotane for any of the above side effects. If they occur you are to immediately stop medicating and call us. We will already have given you prednisone pills to give at home if side effects are significant.

After 7-10 days of loading dose the cortisol levels are assessed with the ACTH stimulation test. Do not give your pet any supplemental cortisone on the day of testing. The pre and post cortisol levels should be normal. If they are, then we will continue to use mitotane at a weekly maintenance dose to prevent the problem from recurring again. Once your pet gets to this point it is rare to need any supplemental cortisone pills.

Two long term effects can occur while on mitotane maintenance therapy:

- The Mitotane can be so effective that the adrenal glands do not produce enough cortisol for normal physiology. This is called iatrogenic hypoadrenocorticism. In these dogs we stop all mitotane therapy and use supplemental prednisone. Sometimes this side effect is permanent, and your dog needs to be on supplemental prednisone the rest of its life.

- It is not uncommon for relapses of Cushing’s to occur within 12 months, even while on the maintenance therapy. These dogs are again given a loading dose of mitotane, then converted to maintenance dose when cortisol levels are normal.Both of these effects emphasize the need for continual monitoring of your pet. This means close observation at home and ACTH stimulation tests every 3-6 months.

This drug controls the symptoms of Cushing’s 80% of the time.

Ketaconazole

This is a drug routinely used to control fungal infections. It has a different mechanism of action than mitotane. It inhibits cortisol production in dogs and humanoids by preventing enzyme pathways from functioning properly. Ketaconazole works for PD and AT Cushing’s. It is not as common to use as the previous 2 drugs.

It needs to be given at a test dose initially to watch for anorexia or emesis. If tolerated well, a loading dose is given for 7-10 days. After an ACTH test to determine if the cortisol is in the normal range, the drug is given every 12 hours for the rest of the dogs life. This is a more expensive proposition than mitotane. We rarely if ever use it to treat Cushing’s.

Surgery

Surgery to remove both adrenal glands can also be utilized. It is an involved endeavor performed at a specialized surgical hospital. Post operative complications are common, and these pets need lifetime prednisone replacement therapy. As a result, this treatment is not commonly utilized.

Radiation

Recurrence of the symptoms of PD Cushing’s after initiation of therapy might be an indication of a large pituitary tumor. MRI is recommended to identify this type of tumor. Radiation therapy is recommended to prevent further progression of symptoms. Unfortunately, there are very few specialty radiation centers that can perform this procedure.

Iatrogenic Cushing’s

This form of Cushing’s is the easiest to treat since we are not giving a medication but taking one away. In most cases the elimination of exogenous cortisone will return your pet to normal function, although this might take several months. Some of the skin changes might take longer, and may not even return completely to normal. In some cases we use a slowly decreasing dose of supplemental prednisone for several weeks to give the adrenal glands time to resume normal production of cortisol.

Adrenal Tumor (AT)

The surgery to remove the cancerous adrenal gland is called an adrenalectomy. It is a specialized surgery that is not routinely performed. Post operative complications are common.

Because the remaining adrenal gland is atrophied the dog needs to be supplemented with prednisone until the gland returns to normal function. ACTH tests are done every few months to determine when the gland is functioning normally, which can take up to 12 months.

Adrenal tumors can also be treated with mitotane at high doses and for a long period of time. Side effects are common at this dose, and relapses can occur. These dogs will also need to be on supplemental prednisone for the rest of their lives.

Feline Cushing’s

Cushing’s in cats is rare compared to dogs. One reason is because they tend to be more resistant to higher levels of cortisol, especially if iatrogenic. Most feline Cushing’s occurs in females. It can affect the ability to control the blood sugar level in cats with diabetes mellitus concurrently.

History

Cats do not show as much PU/PD as dogs do, unless they have diabetes mellitus also. Most cats are presented in a more advanced state of Cushing’s disease because the early symptom of PU/PD is not observed. They might also have hepatomegaly, weight gain, pot-bellied appearance, and muscle wasting. Sometimes the skin is easily bruised and torn. This is called the fragile skin syndrome.

This picture is from an older cat that was at the groomer to be clipped. The skin literally peeled off like wet tissue paper when the groomer attempted to clip some mats. This is a serious problem and does not lend itself to an easy treatment.

Diagnosis

Cats do not routinely show any changes on a regular blood panel or urinalysis. The most consistent finding on a blood panel is hyperglycemia (elevated blood sugar). An elevated alkaline phosphatase occurs in only a minority of cases. Oftentimes the elevated alkaline phosphatase is due to liver changes from unregulated diabetes mellitus.

The urine cortisol:creatine ratio test is helpful in cats, especially since it is a relatively stress free test compared to blood sampling. If the test is normal then there is much less of a chance that Cushing’s is present. It the test is elevated it might be Cushing’s, but there are also other situations that cause this elevation.

The ACTH stimulation test is used, but two blood samples need to be analyzed at 30 and 60 minutes, instead of the 1 sample at 2 hours for the dog. This is because the increase in cortisol is variable in the cat. False negatives are common. False positives occur in stressed cats or those with non adrenal illness.

The LDDS test is used but the dexamethasone that is injected needs to be given at a higher dose. This test, when used in conjunction with the ACTH stimulation test, is one of the best ways to diagnose Cushing’s in the cat.

The HDDS test to differentiate PD from AT has not been refined to the point that is of diagnostic value.

In general, results of these tests can be variable, and must be interpreted in conjunction with the history and clinical findings. In light of the fact that Cushing’s is uncommon in cats, these tests need careful interpretation.

If the above tests suggest Cushing’s then radiology can be helpful since up to 30% of feline adrenal tumors are mineralized. Other radiographic findings include hepatomegaly and obesity.

Ultrasonic evidence of an enlarged adrenal gland (especially if unilateral) or changes in internal adrenal architecture is strong evidence of an adrenal tumor (AT).

Adrenal tumors occur in about 20% of feline Cushing’s. They can be malignant or benign.

Treatment

Medical therapy is generally unrewarding. Ketaconazole can be used, but the effects are variable, and side effects can occur. Mitotane might help, along with metyrapone. Metyrapone may be more helpful as a pre-surgical stabilization prior to surgery. Anipryl has not been used in cats.

Surgery is needed to remove one of the adrenal glands if the gland has a tumor, and both glands if the problem is PD. If both glands are removed the cat has to be on supplemental cortisone (prednisolone) and mineralocorticoids for the rest of its life. Some cats with concurrent diabetes mellitus will no longer have the disease when their adrenal tumor is removed.

Unfortunately, cats with Cushing’s can be poor anesthetic risks due to diabetes mellitus and fragile skin. When this occurs we sometimes will use medical therapy to help control the problem and make our patient a better anesthetic risk.

Even thought it is not often that a dog or cat is presented to us with an emergency due to this disease, if your pet has other medical problems at the same time this is possible. The Long Beach Animal Hospital, staffed with emergency vets, is available until the evenings 7 days per week to help if your pet is having any problems, especially shock, pain, breathing hard, or bleeding.

Think of us as your Long Beach Animal Emergency Center to help when you need us for everything from minor problems to major a major emergency. We serve all of Los Angeles and Orange county with our Animal Emergency Center Long Beach, and are easily accessible to most everyone in southern California via Pacific Coast Hwy or the 405 freeway.

If you have an emergency that can be taken care of by us at the Animal Emergency Hospital Long Beach always call us first (562-434-9966) before coming. This way our veterinarians can advise you on what to do at home and so that our staff and doctor can prepare for your arrival. To learn more please read our Emergency Services page.